Those Who Went Before, and the Community They Helped to Build

By Beverly Faxon

Last summer, two Co-op community icons died, Sherry Broome and Emilie Cunningham. Between them, they had worked at the Co-op for about 80 years. (I feel like I just need to sit with that for a minute.)

One had a calm presence, a love of healing, and the ability to smoothly navigate the Co-op’s financial and technical realms. The other kept us on our toes, kept the shelves steadily stocked for decades, loved to visit with customers, and made the best tea cakes ever.

I just saw the quiet, elegiac movie Train Dreams, shot in Washington and set in the early 1900s. In one scene, the main character travels by train over the old wooden bridge he had helped to build when young—a bridge that had transformed both him and his part of the world. Silently, he gazes downstream at another bridge, a new bridge of concrete and steel, flowing with cars. It was my husband who pointed out both the metaphor and the reality of that scene: how we are surrounded and supported by the work of those who have gone before us, and how that history so often gets swallowed by the busy, self-preoccupied present.

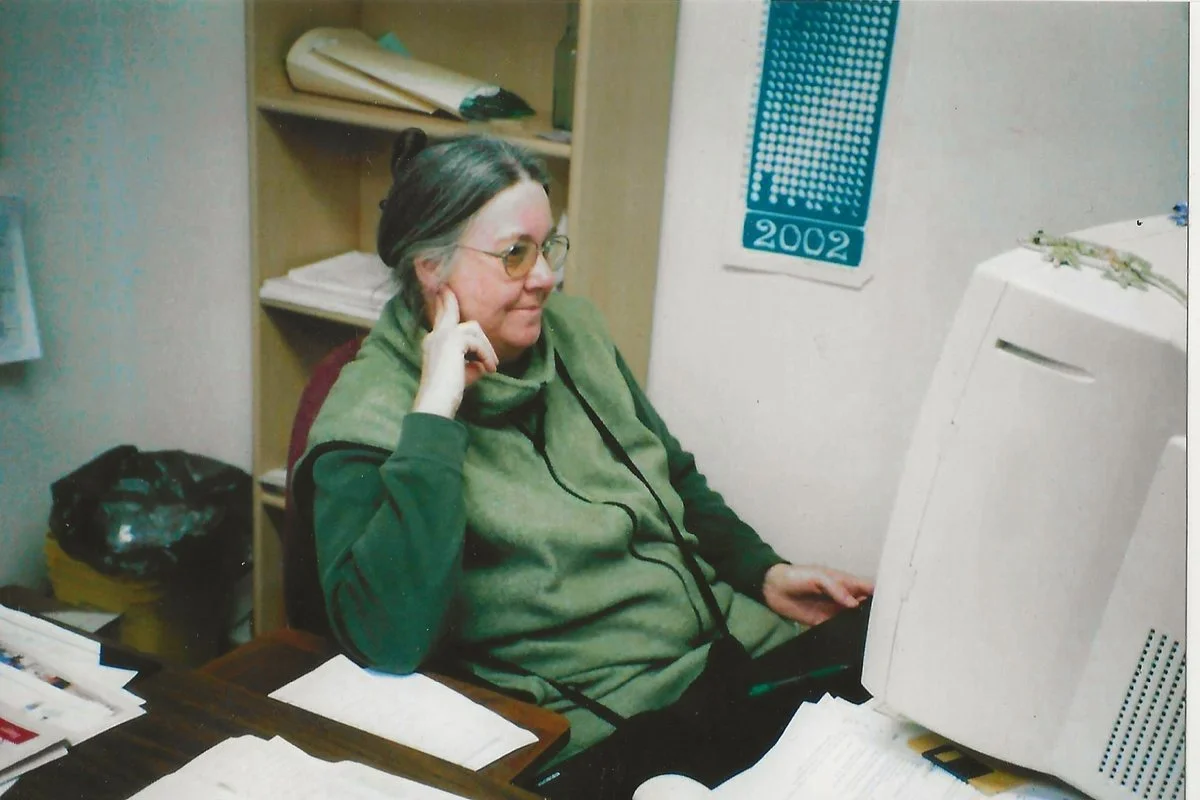

Sherry

Sherry Broome was the bookkeeper and then financial manager of the Co-op, but her influence stretched into every Co-op corner. She started in 1979, when she filled in as part of a paid staff of three for a bookkeeper visiting Europe. As former Manager Todd Wood puts it, “Her style, competent but kind, was a good fit, and in a mild coup, she kept the job after the old bookkeeper came back.”

Sherry’s tenure saw the Co-op move from the small, shaky building on Pine Street to the current location, and then through all the remodels, expansions, and purchasing of the new site that ensued. As financial manager, she was in the thick of it, key to making it happen from an accounting perspective. But like so many jobs in the Co-op community, and even more dramatically in the early days, her efforts spilled beyond her job description. Sherry was just there, carrying what needed to be carried.

Her soft North Carolina accent belied the fact that she could also tenaciously hold onto what she felt needed to be held onto. At her memorial service, a nephew mentioned that he’d never heard Sherry utter an unkind word to anyone. I immediately thought, you never asked Sherry for a replacement stapler. She was the maven and gatekeeper of the supply closet for many years. Misplacing a stapler was not acceptable behavior. She might not be unkind, but she could be steely, and I remember when every stapler, and every pair of scissors, on every desk, had a name taped on it for easy tracking.

Before computers, she also had to manually track the financial records, all on paper. Her office was a marvel.

As Todd says, “Sherry was the savant in piles. It didn’t matter what it was that you needed. You’d go to the office and look around and think, this is hopeless, and you would ask for this particular piece of something, and she’d extract what you needed. I have no idea how she’d do that, but it was her superpower. I knew I could count on her to pull order out of chaos without too much difficulty.”

Storing all those papers became its own project, and I recall her carrying her preferred cardboard produce boxes (apple) up to the third floor, and the towers of those boxes, each packed with files. Even after computers, the boxes accumulated and remained, at first because computer storage was non-existent or dicey, eventually just because... you never know.

But focusing just on Sherry’s office work leaves out her other worlds, and the way they influenced the Co-op, too. Sherry was a healer who studied acupressure and worked with tuning forks. I know I’m not the only person who sometimes went to Sherry’s office in pain and came away feeling better. She held onto the magic of crystals and of the rocks she and her husband David collected and polished. For Halloween, she often dressed as a fairy—tulle, sparkles, wings, and a wand.

The finance office in those years was home to plants and fish and birds. She was one of two people at the Co-op who could be counted on to scoop up a stray someone found, and give it a home. Sherry specialized in cats, who would join the passel she and David cared for at home. (The other person, who still works at the Co-op, will remain anonymous for her own protection against entreaty.)

Babies were welcome in the office as well.

Former Co-op staffer Jenny Sandbo started at the Co-op in 1990 as a grocery stocker, “In 1995, my son was born. Sherry and her mother-in-law, Anne, visited my hospital room, laughing and cooing over the tiny bundle of my baby boy. Her visit made me feel like I was part of a special community. After that, Sherry invited me to join her as a part-time assistant on the administrative team, and surprisingly, I was welcome to bring the baby. When I had my daughter in 1999, she joined us in the office as well.

Both of my babies spent their first six months of life sleeping, eating, and being changed in that office. Sherry would work on her spreadsheets (remember Lotus 1-2-3?) with a baby drooling in her lap. It was a unique situation, one for which I am forever grateful. The Co-op was a community supporting a young mother who was making a living while caring for her family. Sherry was a driving force behind that culture of care.”

Sherry retired in 2020, after 40 plus years at the Co-op.

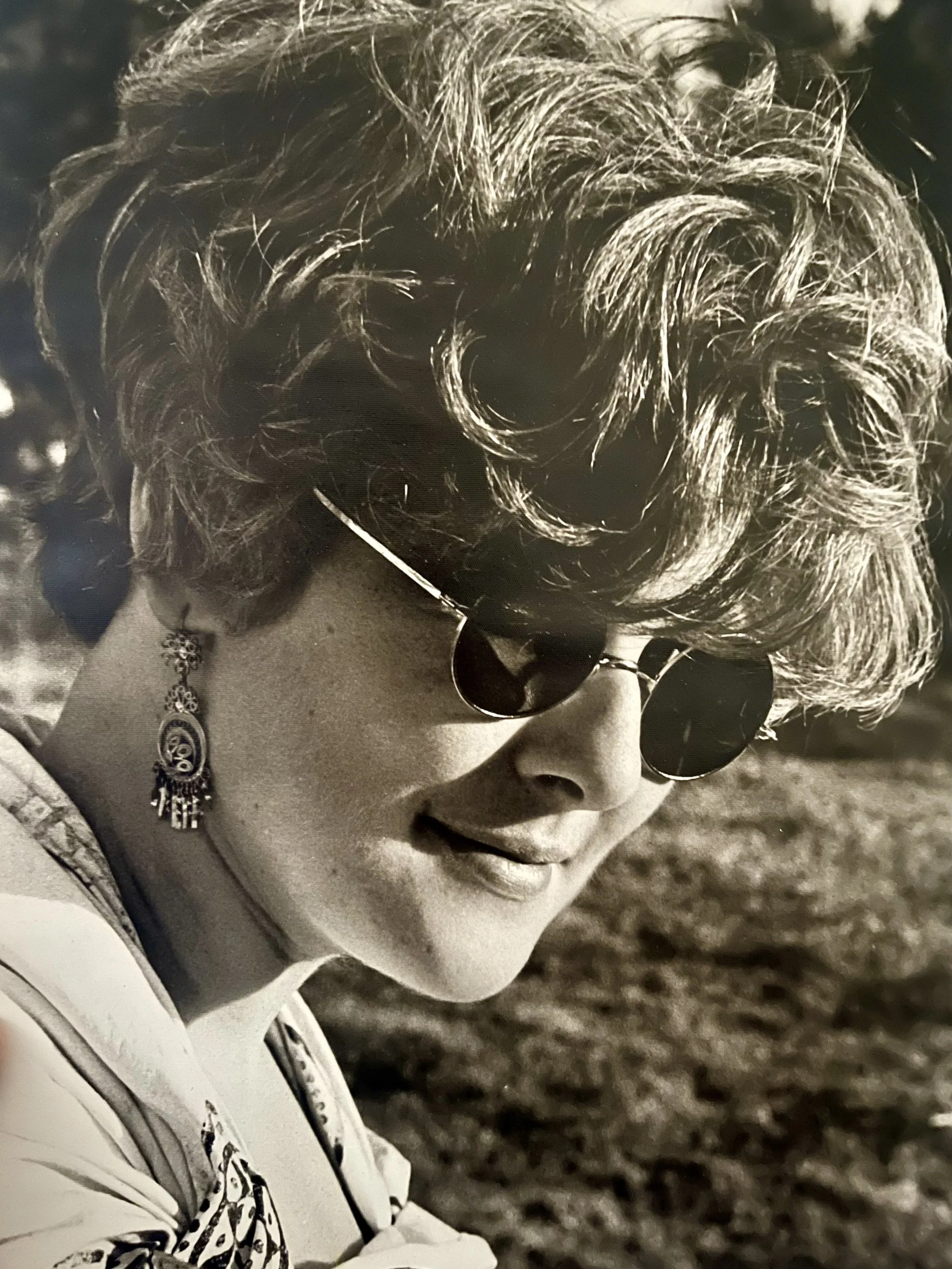

Emilie

Emilie Cunningham never dressed as a fairy for Halloween. Her preference was simple: a pointed black witch’s hat. With a short black cape if she was feeling really festive.

Emilie started at the Co-op earlier than the rest of us can remember, and she stayed at the Co-op until 2013. She was one of the many volunteers in the early days who kept everything going. When I arrived in 1980, she stocked the grocery shelves and the produce cooler—or at least the nine or so square feet of the cooler that made up the entire produce section.

Todd remembers, “The delivery truck would come up from Seattle, and products would be waiting for stocking, spread out all over the place. I remember once when the refrigerated stuff was outside the wooden cooler, all those little flavored yogurts sitting on the floor. And Emilie suddenly got up and said ‘Time for my martini’ and left, leaving the cold products just stranded there on the floor. I was flabbergasted—you just don’t do that. But that was Emilie—she wasn’t going to get caught up in other people’s priorities. She just exuded a flamboyance.”

She was a single mom with two daughters, and Todd says that when he began in 1978, both their names were written, in a childish hand, on the walls of the kids’ play space in the center of the old store. Ora Mae, one of those daughters, remembers two things about the early days of helping her mom at the Co-op: eating yogurt push-ups, and sitting on the floor, putting price stickers on rice cakes.

Ora also remembers that their family struggled financially, and Emilie’s work at the Co-op made a difference, “We lived in a trailer down by Ship’s Harbor and then in a tiny one-room cottage in Anacortes. My mom was on welfare. But we were able to eat good-quality food. Most of the other kids at school were not eating fried tofu with soy sauce.”

Says Ora, “The Co-op helped my mom connect with a wider group of people than she might have otherwise. She met good people with whom she maintained long friendships. As the Co-op grew and became fancier, it was harder for Emilie, an over-the-top eccentric hippie, to fit into the Co-op’s evolving ethos. I’m deeply, deeply grateful to the Co-op for allowing someone as eccentric as she was to have a public-facing job.”

As the Human Resources person at that time, I can safely say that holding your ground with Emilie could be like standing up to a hurricane.

Yet, one of my earliest memories of her was a cold December day in 1980, when I drove down in my old VW van—no heat, no radio—from my home in Concrete. When I arrived, Emilie was already there, and, with tears in her eyes, told me that John Lennon had been shot. It wrecked her that day, such an act of violence, such an end of an era. Says Ora, “She was painfully empathetic. A lot of other things were a way to distract from that.”

As the paid staff grew, Emilie moved into both the grocery department and cashiering. She ordered the magazines and handled the bulk orders. She was a constant presence on the floor, always happy to talk with customers. Her close friend Fran Farnham, former Co-op cashier says, “She knew everybody. She always remembered everyone. Years later, she could tell you their stories—who they were, where they lived, who their children were, who their partners were.”

Emilie was also an artist—she majored in art in college, and then took a job as a technical illustrator at Boeing. She was a painter, yet Ora says she really excelled as a cartoonist, sketching “really brilliant off-the-cuff illustrations that are funny and charming.”

Her granddaughter has inherited that talent. Adds Ora, “She raised us to appreciate beauty and nature. I realize now how extraordinary that was. For me it was the fabric of life, including a love of fine things. She was a poor hippie, but with incredible taste. She should have had a trust fund.”

The work of the present is crucial. At the Co-op, that includes the people upstairs at their desks; the people downstairs stocking, cashiering, cleaning, serving up food; the people behind the scenes packaging, cooking, and baking; the people helping customers on the phone and on the floor. All of them keep the Co-op running.

Yet, holding the Co-op up are the tracks laid and the bridges raised by the thousands who have gone before. In turn, the Co-op has shaped lives and forged a community—with good food, good jobs, a chance to create connection and support, a chance to be oneself and not squeeze into a specific mold.

Says Todd of Sherry and Emilie, “Both of them had big hearts.” And really, what could be more important when building a Co-op, or a community?

Mimi’s Tea Cakes

Every winter, Emilie made the lightest, most delicious powdered sugar cookies, the recipe of her grandmother Mimi. If you got a batch, or even a bite, you felt pretty lucky. Thank you to Emilie's daughter, Ora Mae for sharing this recipe, a closely guarded secret for many years.

Ingredients

1 cup butter

4 Tbsp sugar

2 tsp vanilla

2 cups flour

2 cups pecans or walnuts, chopped fine

Powdered sugar, lots!

Plus, some gallon Ziplock bags

Directions

A food processor works very well to chop the nuts. Stop when they are fine—before they become nut butter.

Beat sugar and butter till fluffy and pastel yellow; blend in vanilla; add flour and beat until just combined; fold in chopped nuts.

Roll into 1-1.25” balls (bigger balls result in a less ideal ratio of cookie to powdered sugar).

To duplicate Emilie’s technique in full, this step is best done while stoned and watching Judge Judy. And/or with a friend who likes to gossip.

It may be optimal to chill before baking, but Em didn’t chill them because there was never enough space in the fridge.

Preheat oven to 325°.

Bake 40 mins or more, check for golden-brown bottoms. This is the key! If you’re impatient, you’ll miss the whole point, which is crisp, light, melt-in-your-mouth cookies.

Cool until warm, but no longer hot. If they cool to room temp, the powdered sugar won’t adhere properly.

Add a cup or more of powdered sugar to a gallon ziplock. Add 10-12 warm cookies and very gently toss to coat them evenly.

Set aside and begin a new bag, repeating until all cookies are coated. They won’t look pretty yet—this is the base layer only.

Before serving, add fresh powdered sugar to the bags and carefully toss again to coat with new “snow.” Emilie gave them to people in the powdered sugar ziplock. Feel free to be fancier if you like.

Do not wear dark colors if you’re trying to sneak a cookie! Everyone will see the evidence on your clothes.